Of the many reasons to restart my blog I expected least the death of a friend. As many of you know, Andrew Grant of AstraZeneca and long-time OpenEye collaborator, passed away on the 29th of December. His death was a total surprise to all who knew Andy: he was fit, ate well and was seldom sick. Still, while jogging in the Spanish hills, he collapsed due to a massive heart attack and could not be revived.

I first knew Andy when I was a post-doc at Columbia with Barry Honig and he was a post-doc with Harold Scheraga, way back in 1991. In those days, to get GRASP or DelPhi you downloaded an encrypted file and then asked me for the password. As the download idea was mine (before that we had to send out tapes!), I chose “newrose” as that password. “New Rose” was the debut single by the English punk band The Damned, a group renowned for doing everything “first and worst” (a habit of mine!). A keen fan of punk, he was incredulous and wrote to ask me if I knew it was a song by The Damned! I really didn’t know much about Andy, I think our only other communication had been my faxing him notes on the Non-Linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation, so I had no idea that instant brotherhood had been struck! He took music that seriously.

I don’t recall many other communications until a couple of years later when we actually met. There was a conference on molecular graphics and modeling in Leeds or York. I sat at the back of the lecture theatre and this red headed bloke came and sat down next to me. “You don’t know me, but I know you,” were his first words to me. Before I thought him a maniac off the streets, he quickly explained he was J. Andrew Grant, who had begged notes from me when I was at Columbia and who had loved the GRASP password. By that time he had moved back to England and was working for the pharmaceutical division of ICI, shortly to become Zeneca. It was instant camaraderie. As any of you know who were lucky enough to form a friendship with Andy, he took such very seriously and we kept in regular contact. He invited me to meet the CADD group at Zeneca, which I still consider the best I ever saw. When I decided to leave Columbia and form OpenEye, it was with the massive encouragement and support of Andrew, and those at Zeneca who trusted his insight.

More than just encouragement, he gave ideas. Before he had settled in Macclesfield he had spent a year in the Wilmington branch, working with Brian Masek. Brian had been playing around with the superposition of molecules represented as fused spheres. The code he had written was slow and prone to getting stuck in local minima, but when it worked it gave strikingly good overlays. While Andy was with Harold, he had been given the task of seeing how one might use Gaussians to calculate a robust and rapid estimate of molecular area—a problem he had not solved. However, he had worked with Professor Barry Pickup at Sheffield University, his PhD advisor, on the concept of representing molecular volumes with Gaussians. In fact, although it is little appreciated, I think that work with Barry and Maria Gallardo, who became his long-time partner, was one of the best ever in the modeling of molecules. It is highly unintuitive that one can use Gaussians to not just represent the volume of an atom (many had been drawn to that concept before) but to use the convolution formula for Gaussians to represent spherical overlaps—to any order! Pure genius. And the result- that you could model the fused sphere volume to within 0.1% is, I do believe, the most remarkable result I have ever seen in our field.

It was for this reason that I began seriously thinking about ROCS (a beautiful result deserves a great implementation). Andy’s initial work along those lines had improved on Brian’s, largely overcoming the problem of multiple minima and decreasing the time required for an overlap minimization from 100 seconds to one or two seconds. This was amazing in of itself, but we both knew it had to be much faster to really have an impact. I proposed aiming for a 1000 per second. I remember clearly him looking at me, not doubting we could do it, but his natural modesty made him suggest we just claim we might be able to do 100 per second, so as not to seem too brash! It was the first example of the Nicholls/Grant dichotomy (me being the brash one). Of course, we eventually achieved that mark and with Matt Stahl’s help made it into ROCS, a product that remains at the center of all we do at OpenEye.

If Andy had done nothing else, his work on ROCS would, in my mind, put in the sparsely-populated pantheon of those who really made a difference in molecular modeling. But in many ways, it was only a minor part of his output over the next fifteen years. Here are, for me at least, some highlights, remembering that this body of work was in addition to the many things he did within AstraZeneca:

1) ZAP. Given such an accurate representation of molecular volume with Gaussians, it seemed natural to imagine using this form for the dielectric constant of molecules. With the help of two students, Paula Kitts and Christine Kitchen, we derived a functional form that worked very well, a form that both reproduced the results from the molecular surface dielectric map in DelPhi, but was much more stable with respect to translation and rotation of the molecule. Both Paula and Christine earned their PhDs from Sheffield with Barry for their contributions to this work. The result was that we could use coarser grids to get the same numerical precision as DelPhi, and so an enormous increase in speed. This was in addition to the faster convergence in ZAP, due to the use of smoother functions. Even many years later it is still not widely appreciated what a breakthrough this was: a couple of years ago we used the ZAP-based protein pKa code Andy and I wrote for the protein pKa blind challenge put together around Bertrand Garcia-Moreno’s work on SNase. People were amazed it took less than a minute to calculate accurate pKas for the whole protein. Over a decade after we wrote the code it was, and is, still the fastest way to make PB predictions. And the work did not stop there; Andy also wrote an interface to Gaussian to allow one to do iterative QM/PB calculations (QZAP) and also helped with the derivation of the first order derivatives of the electrostatic energy—the first time anyone had done this in a robust and fast manner—in fact, he found that forces almost cost nothing compared to the original PB calculation.

2) Docking. A less appreciated, but still wonderful, piece of work that grew out of the concept of modeling hard spheres with Gaussians was the Grant-Pickup formula for shape-based docking, a formula that underlies our FRED docking program. Essentially, Barry and Andy found that a weighted average of a Gaussian function and its first radial derivative gave a function that looked amazingly like the VdW energy of the approach of two spheres. A free parameter, kappa, essentially the width of the Gaussian, controlled the sharpness of this pseudo-energy function—i.e., a small value would produce a shallow minima, a large kappa a steeper one. As such, they could “tune” their function to either the character of VdW interactions or produce a much smoother, less fractal landscape. Mark McGann, while at Johnson and Johnson with Frank Brown, showed that you could tune kappa for real-world applications and illustrated this by optimizing cross-docking pose predictions across a disparate set of trypsin isoforms. Ironically, given its success, Andy was actually less interested this than in what he called “internal docking”. By simply replacing the original function with one in which the two component functions subtracted rather than added, the modified function had Partial Shape-Matching character—that is, if a fragment of a molecule was randomly placed within the parent molecule and this new function optimized the fragment, it could find its way back to itself within the larger molecule. This intriguing finding remains largely unexplored.

3) Gaussian Accessible Area. Having succeeded in calculating the electrostatic solvent forces in ZAP, we looked again at whether we could calculate the accessible area of a molecule. Note that the word “accessible” signifies that this is not the contact, or Van der Waals, surface but the extended surface that represents the loci of a center of a sphere the radius of water rolled over that surface. The problem with using Gaussians for this is that the number of overlaps of these extended spheres became impractically huge, approaching N (Heavy Atom Count) factorial. Instead, Andy and I went back to the oldest method for area calculation, namely that from Shrake and Rupley, which was simply to put dots on each extended sphere and calculate whether such are inside or outside. The problem with this old algorithm was that it took many dots to get an accurate area and had no derivatives. We solved this problem by having such dots sample the extended Gaussians representing each atom. If this sum was above a certain threshold we removed it from the area calculation, otherwise we calculate a “partial” occlusion. Because the sum of extended Gaussians was so smooth we could get away with many fewer dots—the method was again amazingly fast (to my knowledge there is nothing comparable) and we could easily calculate derivatives. Both aspects were important because it meant we could add a non-polar energy term to PB, allowing us to evaluate and optimize continuum theory predictions of binding energies, usually in less than a second.

4) Approximate Solvation Models. Because PB and surface area were now so fast we could compare and contrast to our bête noir, GBSA. This very approximate, and to some of us profoundly distasteful, attempt to estimate the energies of PB was (and unfortunately still is in many quarters) quite rampant. The advantages claimed were that it was simpler to program (true), much faster (suspect) and gave you gradients (which ZAP now did at no cost). We examined GBSA very closely and realized that if you wanted ZAP to be as inaccurate as GBSA you had to choose such a coarse grid spacing that PB was actually faster than GB! This was widely ignored, I think because the other advantage of GB, being able to adjust internal parameters to give you the answer you wanted, was an advantage PB lacked. Eventually, more for fun than anything else, we did construct our own version of GB using, naturally, Gaussians. It was quite elegant and required only a single parameter, unlike the parameter proliferation within the literature. But we never used it in anger; we already had the real thing. The work on GB vs. PB did lead to one very startling discovery that became known as the Sheffield Model. A young post-doc, Matthew Sykes, again working for Barry Pickup and Andy, was engaged to work on variants of our Gaussian PB but instead tried an extraordinary simplification. Rather than calculating all the atom-atom distances required for the shielding and desolvation parts of GB, Matt simply used a couple of universal constants, A and B, and found that the resultant model was almost as accurate as GB (i.e., about as worse from GB as GB was from PB). Considering that this approach required almost no computation, gave easy gradients and was almost as good for small molecules, it seemed a natural to use in minimization code, where it now resides in Szybki. In fact, for entropy calculations in solvent it is actually better than PB (!) because the gradients are so reliable and differentiable.

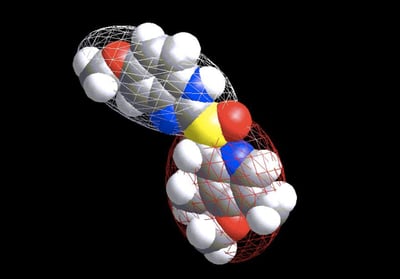

5) Getting back to shape, I think if there was one piece of work Andy himself would most want to be remembered for it is an approach that hasn’t even (yet) made an impact, namely the representation of molecules by Ellipsoidal Gaussians. The idea here was simple enough: instead of using a Gaussian centered at each atom, we would allow a few Gaussians to “float” around and to elongate or squash, so at they could represent sets of atoms (we imagined cigar-shaped ellipsoids for aliphatic chains and disk-shaped ones for ring systems). It proved a real challenge, both mathematically and computationally, to solve this problem in a robust and reliable manner, but I shall always recall the day we got it working. Andy had come over to Santa Fe for a couple of weeks of “vacation” and was working on the loaner SGI from Glaxo that Paul Charifson had organized. By a strange twist of fate it still had a yellow sticker that read “Mill Lambert” (Mill had been a colleague from Andy’s Scheraga days). After a frustrating week of working on the problem he called me over in his typical low-key way: “You might want to take a look at this.” There on the screen was a beautiful two-ellipsoidal representation of Omeprazole (attached below). It was like seeing a goal by Eric Cantona for the first time. We subsequently improved the approach so we could construct quite elaborate, multi-ellipsoid, representations, coloring their surfaces, working out the mathematics of overlap between two sets of such and the derivatives with respect to position—but we never quite found a use for them! The mathematics was expensive so there wasn’t much of an advantage over ROCS. There were often different (quite reasonable) representations of a single conformer. And sometimes it took a lot of them to really capture a shape. The best use we ever envisioned, and actually published upon, was as an anonymization technique: i.e., you could obscure what the underlying molecular structure was but keep the shape. I hope this, or some other use, one day catches on as I know it was Andy’s favorite piece of work.

6) Around the time he and I were perfecting ellipsoids, OpenEye hired James Haigh, ostensibly to work for Barry Pickup as a post-doc but more to help Andy with his many projects. Although initially suspicious about this free help, James and Andy quickly because very productive together. Their best work was on the exploration of Shape Space: i.e., seeing how many molecular shapes up to a given size where needed such that any subsequent molecule had to be within a certain shape distance of a molecule already seen. They discovered that for a given threshold of similarity the number of such shapes grows in an almost perfectly exponential manner with respect to size. By comparing to hypersphere results we could estimate that the effective dimensionality of shape space grew roughly as the number of heavy atoms divided by three—a remarkable result. It led to the concept of a shape fingerprint, a string representation of ones and zeros where a bit was set to one if a conformer was within a threshold of similarity to a particular “reference” shape. Shape fingerprints proved a pretty good surrogate of shape, but the original concept of shape space proved the stronger concept, going on to influence the design of chemical libraries, in particular in the work Andy did with Neil Hales. Another interesting aspect of the work on shape was to show that the shape tanimoto obeys the triangle inequality. This work was done as a part of Huw Jones’ Sheffield PhD project that also encompassed the examination of RMSD between conformations as a distance metric.

7) Returning to electrostatics, work with David Timms on Lck kinase threw up an interesting observation still not widely appreciated, namely that some series show SAR in parts of the molecule that have no contact with the protein; this is purely a through-space effect of the protein potential (as calculated by PB) and the functional group being modified. It was a lovely piece of work, hampered only by the limited amount of data AZ was able to generate. This limitation in data quantity led to its rejection by J. Med. Chem., in my mind one of the poorer decisions made by that journal. The quality of the data, I think, was sufficient, and the concept compeling enough that the work could and should have been examined by a wider audience. I still hope that happens to what Andy and I always referred to as the Timms Effect.

8) As well as pioneering the ROCS concept, Andy was a big believer in the expansion of shape comparison toElectrostatics Field Comparison. We always assumed that having “pure” physical quantities, as opposed to ones constructed from atom typing, would be superior, and were always disappointed when virtual screening studies suggested the opposite. However, like all true believers, sometimes you have to wait awhile for reality to catch up to your faith! And when it finally did we were delighted to see examples such as Grant Churchill’s discovery of a nanomolar NAADP mimic. That this work was done by an undergraduate in Grant’s lab as a summer project only emphasized to us that this was a robust, intuitively correct concept. And, only a couple of years later, Andy had a successful “EON” hit of his own with a fibrinolysis inhibitor, discovered almost “off-the-shelf” that no other method had found. Although it did not make it into development, largely because of commercial decisions, it was gratifying for Andy to see this elementary, physics-based method deliver.

9) The last piece of substantial work Andrew did was on Molecular Dipoles. For several years he had been aiding my work on solvation energy prediction, regularly computing high-quality QM charges for use in the SAMPL challenges. It was that careful work that demonstrated to us that better charges usually got better (PB) results—a nice result but a frustrating one as some of the QM calculations were taking months. To see what the appropriate level of calculation ought to be we turned to a different physical property, dipole moments, where we could be sure of the experimental result (or so we thought). To get this data, Lisa Chubrilo carefully transcribed hundreds of results from the compendium of McClellan. To our surprise, the agreement with QM, even at a high level, was not that great. Although there seemed to be a core set that were well predicted, there were dozens that were not. This led to a lot of soul-searching and a lot more diligent work by Andy and by Maria, who discovered that sometimes these outliers were the result of poor proton positioning by OMEGA, sometimes the conformation was wrong, and sometimes the literature was incorrectly transcribed into McClellan (we never found an example of Lisa mis-transcribing from McClellan!). With all of these examples cleaned up we could see a very strong signal—DFT always gave superior results to Hartree-Fock calculations for the same basis set, and we could also see a real sweet spot where the calculation was both accurate and fast—something not yet fully exploited in our work. Finally, we also came to realize that the claimed accuracy of experiment of 0.01Debye was too low, both because very high level calculation never improved beyond an RMSE accuracy of 0.1D, and because we saw enough papers by different groups on the same molecule to realize that 0.1D was a much more realistic experimental error.

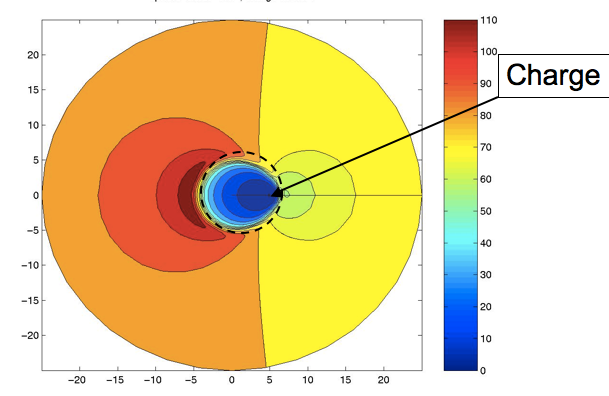

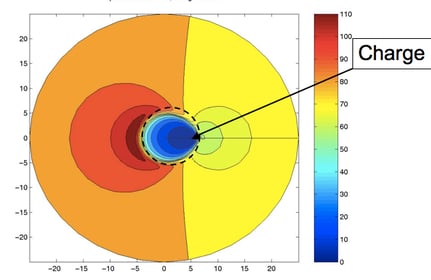

10) I want to end with perhaps an unlikely example. I’ve not mentioned several internal pieces of work at AZ, such as his exploration of the LINGO similarity measure, or his amazing notes on quaternion adaption, or his aid to Peter Taylor’s tautomer work, or any of a number of great talks he gave at meetings. Rather, I want to end with a small piece of science that he and I did that illustrates his love of mathematics. From my early work with GRASP I had noticed something interesting in the Effective Relative Dielectric, the uniform dielectric that would be needed to reproduce the potential from a charge at one atom measured at a second, distant, atom. If these two atoms were in a protein, the effective dielectric was small when the atoms were close, but would increase if the atoms were far enough apart for solvent to have an effect. What was surprising was that the maximum of this function was typically larger than that of water—i.e., a low dielectric mass (protein) embedded in a high dielectric (water) actually could create over-screening. This was especially true when the second atom was on the opposite side of the protein. This was considered by some major figures in the field to be a mistake, a consequence of incomplete convergence or a grid spacing problem. Actually it was quite real and might have interesting biological consequences: proteins with a net negative active site often have a large positive area on the opposite side of the protein and vice versa. To prove this was a real effect, Andy implemented the analytic solution for the PB equation for a charge located just beneath the surface of a sphere and calculated the contours of effective dielectric. When plotted, this beautiful figure clearly showed an antipodean zone of an effective relative dielectric of over 110. I have appended his illustration below. This picture and the simple two-ellipsoid fit to Omeprazole are images that I shall always associate with the work of J. Andrew Grant. Simple and elegant, with an eye for the beautiful, but practical, result.

I hope this illustrates why his death is such a loss for the field of molecular modeling. Even without ROCS he made such major contributions, not all of which have yet played out. But even that loss does not compare to the loss of our dear friend, someone who put up with us camping out at his house, who always had time to help with projects, to freely exchange ideas, to see the bright side in people—which he did despite severe provocation! He was tremendously witty, a natural sportsman, could write like an angel, loved music and Manchester United with a passion, was widely read and appreciated greatness, wherever it lay: in a great goal, a great song, a great piece of art or a wonderful piece of science or math. He was a universally liked man, and I only wish more of you had had the chance to get to know him.

Anthony

Preserved Comments

Back when AZ at Alderley was still ICI Pharmaceuticals, about '91-92 I guess, we got permission to hire a computational chemist and I went looking. We had a few people in, none of whom really fitted and we were about to advertise again when Andy's cv landed on my desk. I phoned NY where he was a post-doc only to find he was back in England but whoever I spoke to didn't know where. So on an off chance I phoned Barry Pickup to ask him if he knew where Andy was and he said yes he's here working with me. Not long after I got a call from Andy and asked him to come for interview at Alderley Park. At first he was reluctant because he had no talk prepared (these were pre-powerpoint, glass slide days) and he didn't have a suit. I told him we didn't care what he looked like, he should come as he was and we'd give him a pen and a white board so he could tell us about his work. So early the following week he turned up in a big woolly jumper with the label sticking up at the back, we gave him a pen and off he went. He stood in front of the white board for an hour or so and talked in that self-deprecating, dry and humorous way of his while scribbling equations and graphs from memory, fielding the tough questions he got with ease. The next day we hired him.

Once he joined us properly, he was still working on the Gaussian's and I gave him time to finish. It took a lot longer than I hoped, 6 months I think, and conscious of the need for him to develop some career points (and cover my rear end) by working in discovery projects I leaned hard on him to "get it finished". He wouldn't budge though until it was done right, tested properly and written up. His priorities were always about doing the work right rather than good enough. I remember those first 6 months very clearly. There was an elegance and purism to his thinking and his approach to solving problems that I envied. So much of what we do in CADD is workmanlike and pragmatic. Andy wanted to get to the truth while many of us are content to accept correlation. The work on Lingo's was unusual for him. I thought it was very clever and obviously practical and useful to "the chemists", and Andy knew that and it pleased him, but he was a bit embarrassed about doing it I think.

During those first six months, Andy introduced us to Anthony, who was in between his post-doc and starting what became Open Eye. Anthony explained his ideas for "High Throughput Modelling" and working with Andy on Gaussian shape. This was around the start of their highly productive collaboration, which over the years has benefited drug design and drug discovery across the industry in ways which I doubt will ever be properly recognised. Anthony and Andy together complemented each others skills, combining innovation, vision, rigorous scientific standards and delivery. A great combination, smart people, good people.

I will miss Andy. I used to catch up with him when I could after leaving what became AZ and always enjoyed spending time with him. He was good company, he made you think for long after you'd met him and I always hoped that one day there would be an opportunity to work with him again, to recapture some of those moments when when he would take over my white board and scribble differential equations and I would try and keep up with him. I can't say how sad I am that that won't now be possible.

Thank you Anthony for creating an opportunity for his friends to remember him

David Leahy

Anthony,

What an eye opening person Andy was. I was lucky enough to get to know him in the brief time that I worked at KuDOS, a wholly owned subsidiary of AZ at the time. I first met Andy and another colleague, Dave Cosgrove, when I visited AZ to look to see if we could integrate some of the AZ prediction tools into KuDOS. What a pair they turned out to be and what a real surprise it was to see the fantastic work they'd put together around the OpenEye tools. I have to admit that this was also my first exposure to the OE software. The following OE UGM, immediately after the Sheffield meeting proved another occasion to be exposed to both again, and I think the first and only time we got to meet in person.

I recall one final occasion when I got to work with Andy, via his participation in the joint AutoQSAR project between AZ and Accelrys. In that time, I think we had one brief opportunity to meet face to face, but his input and affect on the project was ultimately for the better.

I can't claim to have known Andy anywhere close to your level, but on the few occasions I got to work with him, his brilliance was evidently clear. Reading your blog, it shows that I saw only a small part of that - and I share in your sense of loss of such a talented mind.

Thank you Anthony for sharing your tales of Andy.

Adrian.

Many thanks for writing this very nice blog for Andy. I still can't believe he's passed away and I am still shocked about it. I left AZ 4yrs ago now, but still I have been in contact with the CompChem group since then, strangely being a crystallographer. I can still remember his face in front of me. He have met so often on a weekend in Macc. He was one of those friendly open persons who made me feel very welcome amongst the CompChem group. Often we played 5 a-side football at Hulley's and as one said before you need a red-headed player in your team to be able to score. Andy was a great friend and scientist.

Yesterday I received the order of service for Andy. I only wished I'd have known before I'd have made the effort to come over for Andy. Can't believe you're gone ... Cheers Stefan

I'm sorry for I didn't know Andy at all till I read ROCS manual first time. At that time

I was noticed that he contributed so much for foundation of OpenEye. I met Andy

first time when Anthony invited him as a speaker to JCUP on 2010.

After the meeting we could go around Kyoto for sightseeing which he seemed to be

enjoyed. I remember he wanted to come to Japan once again. - Takehiro Oh

Thank you, Ant, for a moving tribute to Andy.

I will remember Andy for both his brilliant work and his intellectual generosity. His work was essential for a key piece of technology in my lab: Projects were made possible, and papers were published that simply would not have happened without his work. I refer to a complete, accurate and fast PBSA treatment of solvation in molecular dynamics. In the process of developing PB theory and DelPhi at Columbia with Ant and others in Barry Honig's lab, I conceived the goal, encouraged by Steve Harvey, of putting PB forces into MD. Some of us were a bit appalled to find out that the 'dielectric' of the highly touted explicit water models was often 40 or less. I even made the MD-PBSA project a big part of my 'chalk-talk' when applying for jobs. Luckily, progress on this was not essential for my career, as it turned out to be effectively impossible at the time! Meaningful progress required Andy's incisive work on Gaussian shape description. In FDPB implementations, it turned out that the trickiest part of the whole thing was making a good representation of the molecule-water dielectric boundary, and doing it fast. The faster Ant and Mike Holst made the actual PB solver, and boy was it fast, the more this mattered, to the point where even making the PB solver take 0 cpu seconds would not effectively speed up the code. Solving PB several dozen times for energy applications was one thing. Solving it millions of times for MD, and then extracting forces was another. Even worse, small changes in conformation between MD steps produced boundary grid-mapping fluctuations which, though effectively averaged out for energies, basically killed MD forces and my goal.

Fast-forward to Andy's elegant paper with Gallardo & Pickup (J. Comp. Chem., 17 (1996) 1653.), and then his implementation, with Ant, in the OEZap libraries. Implementation is everything. It was fast, stable, gave accurate forces, and as an extra bonus, it gave the surface area and its derivatives 'for free'. As Ant has said, the degree of breakthrough is perhaps unappreciated. For example, if we hadn't had the area terms, then putting the non-polar force terms into MD-PBSA using existing area routines would have pretty much negated any advance from the smooth permittivity part. This all stemmed from Andy's original insights. Once Ant sent me the libraries, I found, as an added bonus Andy's interface code stub. Now interfacing was easy as pie! Within a couple of hours I had both AMBER and CHARMM hooked up to OEZap, and fast, realistic solvent treatment in MD was now possible. When I later enthused to Andy about it all he was typically modest. As a small side note, when implementing the PBSA in the MD codes, being lazy I just pirated their existing GB code elements, with minimal name changing. I think Andy would have derived some amusement from the fact our versions of CHARMM, AMBER lie when they run, they are not doing GBSA, but PBSA!

Finally, I have long had an interest in the history of thermodynamics, physical chemistry and biophysics. I have been collecting classic original papers, some dating back to 1850's, but more modern ones too. I find reading and re-reading the original work, seeing how the authors lay out their arguments, gives me a sense of knowing them better as scientists. Andy's paper on Gaussian representation of molecules is among my collection. So long Andy.

Kim Sharp, January 2013, University of Pennsylvania

Great eulogy ant, great read and really shows what a big contribution Andy was and is to our field.

I am yet another of those that first met Andy in an interview alongside Sandra and was then lucky enough to be involved in his work on molecular dipoles ant mentioned. I owe a lot to andy and will remember him as one of many inspiring figures from my year at AZ.

He also inspired my latest craze of turtle neck jumpers! - Joshua Meyers

Thx for writing that, a moving & impressing piece.

Guess who made the best presentations at the internal AZ CC workshops? Mixed equations with philosophical statements? Made even the most conservative chemists try out some new hack? Whose attitude still serves as example to all, not onlly fellow collagues & nerds! - Planet Broom

First, thanks Ant for the wonderful eulogy for Andy.

I met Andy when he came to work at AZ in Wilmington and had the pleasure of discussion some great science on solvation, shape, and electrostatics when we commuted together. But my strongest memories are of Andy coming to the house for dinner and spending the afternoon in the backyard patiently chasing a soccer ball with my son.

Truly sad we lost a great person and great scientist.

Brian

Thanks Anthony. Everyone has their own memories of Andy, my first is when he interviewed me here at AstraZeneca. I turned up expecting a grilling but what struck me most about Andy was how keen he was for you to do well. He gave you all the encouragement you needed through his personality and questions for you to come out thinking that you couldn’t have done anymore. Although clearly his scientific skills form many of our memories of him, my fondest memories of Andy are from our group Secret Santa which I organise each year. Now many people may think that Secret Santa is very simple, however, experience has suggested otherwise so I maintain 'The Rules of Secret Santa’ on an internal wiki page to make sure there are no unexpected problems. By 2009, I was up to 12 separate rules to make sure people knew how it worked and to foresee any issues that may come up. That year Andy came into my office, looking a bit sheepish, informing me that although he had pulled a name out of the hat as usual the previous week, he had not only forgotten the name, but had chucked away the name which he had taken. Not foreseeing such an event a solution became apparent to us. Firstly, I had to wait until the day of our Christmas meal to check who had no present to identify the name he had pulled out for him to go on a late present buying mission (he had at least checked that he hadn’t selected his own name). The second result was my addition of ‘Rule 5b’ the following year instructing people to keep the names of the person they drew out somewhere safe. That’s Andy, always pushing the boundaries and stretching you… - Raw883

I had the pleasure of meeting Andy at the first AZ Comp. Chem conference and agreed with him that Dave Cosgrove coming to Boston would be a good opportunity for Boston and Dave. Needless to say it was good for all involved and I had the pleasure of working with Andy on AZ projects. He will me missed but his spirit will continue to inspire those who were fortunate to know him. - Ken Mattes

I first met Andrew during my job interview at AstraZeneca. He and Sandra McLaughlin were the last of many interviews. They made such a double act as they finished each other’s sentences; it felt more like an informal chat than an interview. Needless to say meeting Andrew & Sandra made my next decision easy.

My three years working with Andrew let me see many of his great attributes from scientific to how to work within industry. I fondly remember the projects we worked on together, one of particular note was a chemistry cartridge for MySQL. He was so eager to work on this he was at my desk waiting for me to continue our pair programming. I'm quite sure he had been assigned some managerial task but was much more interested in coding. One aspect of this cartridge was the LINGO similarity measure that Anthony mentioned, which continues to be used daily by internal AstraZeneca systems.

My lasting memory of Andrew will be my penultimate day in the UK before moving to New Mexico. Andrew, a few friends and I were out for breakfast, which stretched to lunch and beyond. As we moved from one restaurant to another, guessing we outstayed our welcome after four hours for breakfast in part because of heavy snow fall. Andrew decides to start skidding along the slippery path as we head towards the traffic of Manchester. While we are panicking he is going to fall, he calmly suggests, with a grin, that we get hold of a football to kick around - knowing full well none of us even followed football, let alone ever kicked one. - Craig Bruce

Well said, Ant, and all I can add is that only Andrew could have inspired us to play football at mid-day in White Sands back in 1998. I still can't quite believe that he is gone and he will be missed by many. - PWKenny

Shortly after joining OpenEye, I visited Andy at AZ for a week or so to learn about the inner workings of our old protein_pka code, one of his many contributions to our code. Andy was very generous with his time and showed great patience when answering my naïve questions. He also showed me around Macclesfield, took me out for some good meals and a few beers, and even lead me on a few memorable hikes in the countryside. The gift of his time and attention—he was a busy man—was above and beyond the call of duty. But that's just the way he was. - Mike Word

Thanks for writing this Anthony. My story is not near the calibre of yours, but I need to get it out. Hope that's okay. Andrew often teased me about my English...and my hair...and my designer clothes...and music taste...and in fact anything that he had read about Sweden (I can't remember how many times he said, when arriving at the Mölndal site for a visit, that ”he was 80% fukt at the airport this morning” (fukt being Swedish for humidity). But here it goes. The first time I met Andrew was 1997, at a model(l)ing meeting in Erlangen, Germany. I was presenting a poster and no one (and I mean no one) stopped at mine, until late, when a guy with red hair started to ask a million questions. Being a student that could have been horrific situation, but Andrew was asking in a very polite manner. Not only was he nearly overly polite, almost excusing himself when asking, he thought the poster was really good. It felt good. One reason for his nice words was that Andrew saw things in what I had done that I did not see myself, a pattern that would repeat itself over and over again the next 16 years. After the model(l)ing meeting I think I sent him my poster and then nothing happened...until I joined AZ a couple of years later. Almost immedately after joining we had a cross-site meeting and a friendly and familiar guy with red hair appeared. It was my very good friend to be Andrew. At that meeting (and most other meetings) Andrew stod out, always ready to provide comments, advice and challenge people who could take it, and ready to defend anyone who could not. His own presentations were often entertaining like stand-up comedy, only it wasn't comedy it was brilliant science. We quickly realised other common interest (than computational chemistry) – football, and he convinced me to come to Manchester and work with him. My best career decision ever. Andrew taught me so much during the 6 months visit. The AP environment was excellent and I agree with you Anthony that the people in the AP group back then with Andy, Phil Jewsbury, Pete Kenny, Jeff Morris, Tony Slater, David Buttar, Paula, Sandra, Huw, etc is the best compchem group I've ever seen. On top of all the fun science and programming we did at work, Andrew arranged so I could see Man U play at Old Trafford (15 times during 6 months – what a gift!). The seats were often apart and Andrew always offered me the best seat, his own seat. But I could never take his seat (and I learned quite few new words standing among the hardcore fans). Andrew was unselfish always giving other people credit...and a caring friend. Always asking how my wife and kids were. After having gone back to Mölndal we spoke regulary and worked on many, many projects together. He was always ready to provide advice and discuss new things.

It feels so unfair and unreal not being able to call him anymore. Quite often Andrew said that he had to do something and that he'll back shortly. And I waited, happily. This time I fear the waiting will be unbearble long. - Jonas BostromI remember Andrew mentioning he'd seen your poster and then sent me a copy of the paper from it. We both knew it was great work and that you'd do great things. His eye for good science was always a keen one. - Anthony Nicholls

Over the years, I've come to realize that I never really knew Andrew. Just when I started thinking I did, I would uncover another amazing piece of work or hear some interaction with a colleague or friend or student that left me gobsmacked. Most of what I do everyday is to sit on the shoulders of giants and take baby steps ( what's the cricket version of being born on third base and thinking you hit a triple, anyway? )

Most mathematicians know what their Erdős number is by heart; this is the collaborative distance between themselves and Paul Erdős, a massively prolific mathematician who simply loved solving problems and would do it with anyone who asked. I expect this is also true for computational chemists and Andy. Through no fault of Andrew himself, I am honored to have a Grant number of 1 - and of course there is a story.

We needed to send some largish amount of data across the pond for Andrew to cogitate upon so I threw it up on my website and, just to see what would happen and if science actually beats the home-team, I set the password to "Chelsea4Ever". Anthony thought Andy would physically harm me but this is what really happened:

----

From: ANDREW GRANT

Re: Public Drop Box

BrianThanks for setting up the public drop box - much appreciated, all worked fine, no issues to report.

Apologies to Ant that only 19 calculations are complete - more tomorrow.

| Password: Chelsea4everI hope all is well Brian and we should not be overly concerned with your apparent infatuation with the young Ms Clinton. Men in white suits for Brian,

All the best Andrew

-Brian Kelley

Thanks Ant for posting this. You did an excellent job of capturing his many contributions to OpenEye and to the field as a whole. I'd also like to mention that in addition to his great work detailed above, Andy was a major contributor to the early directions of VIDA. In my first two years at OpenEye, I spent nearly an hour a day on the phone with Andy discussing the focus and functionality of VIDA, and in particular, how it was being used internally at AstraZeneca. With the singular exception of Mark McGann (with whom I shared an office during that time), I'm pretty sure I may have talked to Andy more than anybody at OpenEye for long stretches during those early years. He certainly will be missed. - Joe Corkery

I appreciated Andy not only as a bright scientist but also as a man with a subtle taste of humor.

I met Andy in in late Fall of 2002, when I presented an initial report on MMFF94 force field implementation at Alderley Park site. Andy quickly learned that I have a specific attitude to WWII and the German army in particular, so he mentioned to me:

"You know Peter will be here, so it will interesting to watch both of you", or something like that.

Those who know Peter know well what I am talking about.A year later in 2003, I was presenting the final report on MMFF94 implementation at Alderley Park. Presentation went well, but for some reason there was no laserpointer at hand, so I used a plastic spoon instead which I spotted on the table. I or somebody else probablly used it during the coffee break. Few months later, on the other occasion, don't remember at CUP, or possibly at one of OpenEye meetings when Andy was in Santa Fe, and when I was about to make another presentation, Andy said to me: "Sorry Stan, I can't offer you your favorite pointer this time".

After the 2003 meeting at Alderley Park, a number of people including Andy and myself , went to a Macclesfield drinking place, which name I don't remember. Most of the people had beer or wine, but I was attracted to the info displayed in the menu that two glasses of a specific cocktail can be purchased for a price of one. I passed that info to Andy, and he asked me with a gentle smile: "So you want a double cocktail?" I replied "Yes". He ordered it for me, and pretty soon I started to feel the effects. The cocktail name was "Zombie", and it was a mixture of many colored alcohols...

I agree with Joe: Andy certainly will be missed. - Stan Wlodek